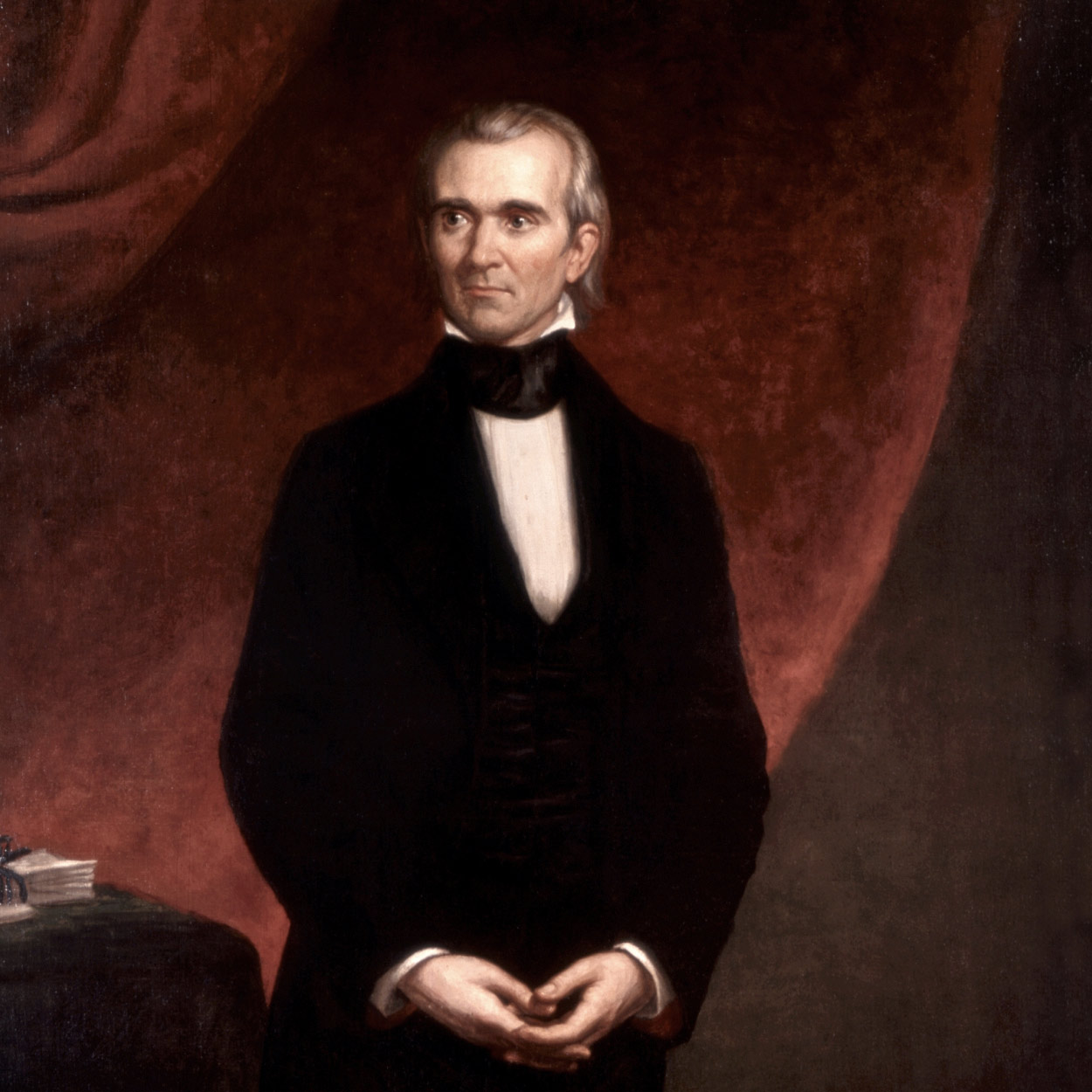

James K. Polk

The 11th President of the United States

(1845-1849)

Often referred to as the first “dark horse” President, James K. Polk was the last of the Jacksonians to sit in the White House, and the last strong President until the Civil War.

He was born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, in 1795. Studious and industrious, Polk was graduated with honors in 1818 from the University of North Carolina. As a young lawyer he entered politics, served in the Tennessee legislature, and became a friend of Andrew Jackson.

In the House of Representatives, Polk was a chief lieutenant of Jackson in his Bank war. He served as Speaker between 1835 and 1839, leaving to become Governor of Tennessee.

Until circumstances raised Polk’s ambitions, he was a leading contender for the Democratic nomination for Vice President in 1844. Both Martin Van Buren, who had been expected to win the Democratic nomination for President, and Henry Clay, who was to be the Whig nominee, tried to take the expansionist issue out of the campaign by declaring themselves opposed to the annexation of Texas. Polk, however, publicly asserted that Texas should be “re-annexed” and all of Oregon “re-occupied.”

The aged Jackson, correctly sensing that the people favored expansion, urged the choice of a candidate committed to the Nation’s “Manifest Destiny.” This view prevailed at the Democratic Convention, where Polk was nominated on the ninth ballot.

“Who is James K. Polk?” Whigs jeered. Democrats replied Polk was the candidate who stood for expansion. He linked the Texas issue, popular in the South, with the Oregon question, attractive to the North. Polk also favored acquiring California.

Even before he could take office, Congress passed a joint resolution offering annexation to Texas. In so doing they bequeathed Polk the possibility of war with Mexico, which soon severed diplomatic relations.

In his stand on Oregon, the President seemed to be risking war with Great Britain also. The 1844 Democratic platform claimed the entire Oregon area, from the California boundary northward to a latitude of 54’40’, the southern boundary of Russian Alaska. Extremists proclaimed “Fifty-four forty or fight,” but Polk, aware of diplomatic realities, knew that no course short of war was likely to get all of Oregon. Happily, neither he nor the British wanted a war.

He offered to settle by extending the Canadian boundary, along the 49th parallel, from the Rockies to the Pacific. When the British minister declined, Polk reasserted the American claim to the entire area. Finally, the British settled for the 49th parallel, except for the southern tip of Vancouver Island. The treaty was signed in 1846.

Acquisition of California proved far more difficult. Polk sent an envoy to offer Mexico up to $20,000,000, plus settlement of damage claims owed to Americans, in return for California and the New Mexico country. Since no Mexican leader could cede half his country and still stay in power, Polk’s envoy was not received. To bring pressure, Polk sent Gen. Zachary Taylor to the disputed area on the Rio Grande.

To Mexican troops this was aggression, and they attacked Taylor’s forces.

Congress declared war and, despite much Northern opposition, supported the military operations. American forces won repeated victories and occupied Mexico City. Finally, in 1848, Mexico ceded New Mexico and California in return for $15,000,000 and American assumption of the damage claims.

President Polk added a vast area to the United States, but its acquisition precipitated a bitter quarrel between the North and the South over expansion of slavery.

Polk, leaving office with his health undermined from hard work, died in June 1849.